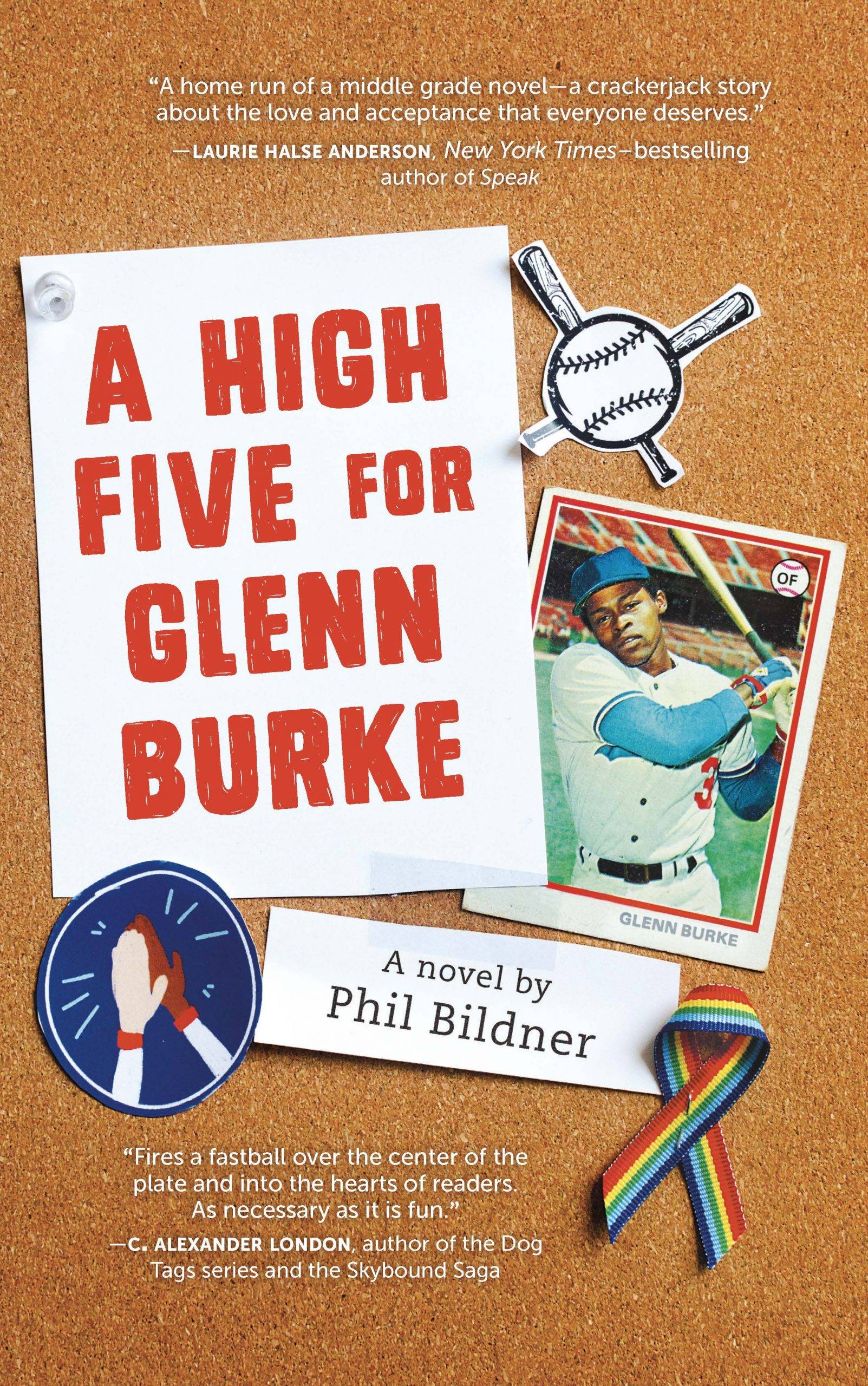

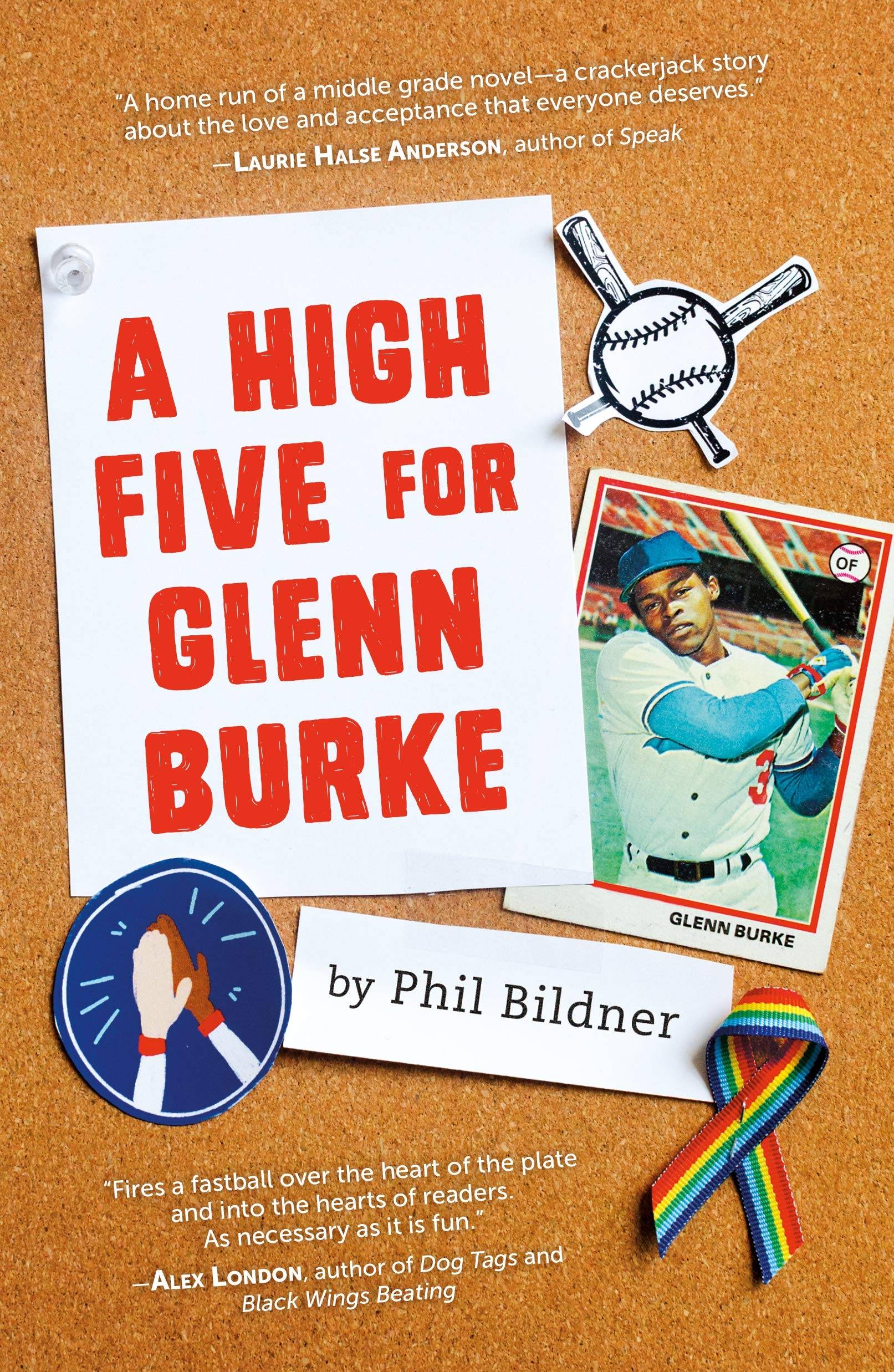

A High Five For Dad, A High Five For Glenn Burke

My dad will never read my new middle grade novel, A High Five for Glenn Burke. Even if he does, he won’t remember it. He has dementia.

I said goodbye to my dad last summer on July 16. Well, I said goodbye to a version of Dad because I knew the next time I saw him – in a week, or two weeks, or a month – there was a chance he wouldn’t know who I was.

A week earlier, the medication he was taking to slow the progression of the insidious disease stopped working. The blockers holding in place his card catalog of life gave way, scattering his memories. The deterioration was sudden and shocking.

Devastating.

If not for my dad, I could have never written A High Five for Glenn Burke. He is responsible for my love of baseball.

Dad grew up a Brooklyn Dodgers fan.

He used to tell me stories about Pee Wee Reese, Duke Snider, and Jackie Robinson and how he would go to Elsie Day Games at old Ebbets Field.

We bonded over baseball.

We bonded over the New York Mets.

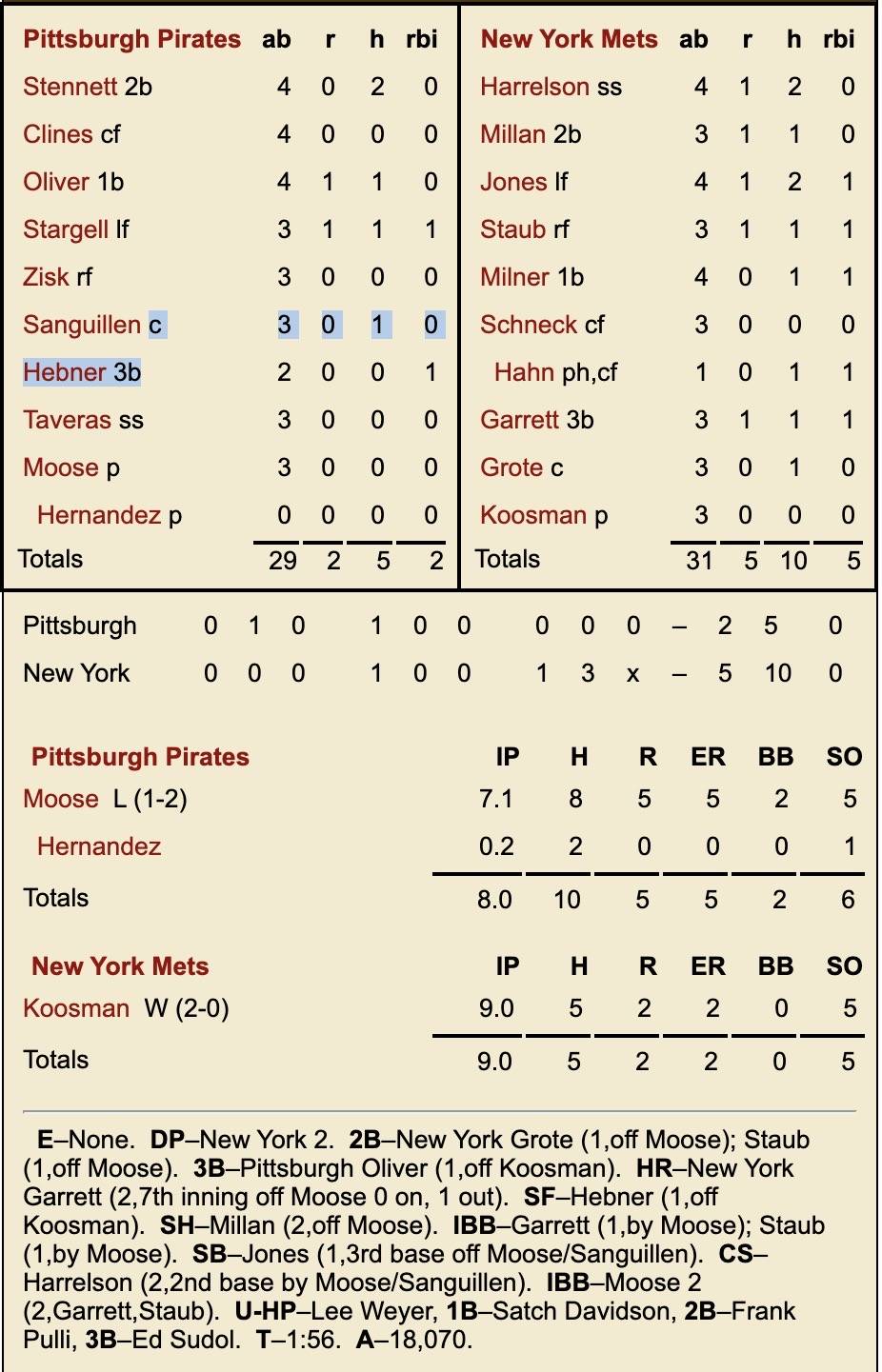

He took me to my first game on April 20, 1974.

It was the first Saturday after tax season. Dad was an accountant and worked Saturdays during tax season. Then again, he worked every day during tax season, and tax season seemed to get longer and longer and longer every year.

The game that day didn’t start until two-fifteen, but I needed to be at Shea Stadium before noon. I didn’t want to miss a thing. We walked up the ramps to our seats, and when that field appeared before me for the first time, it looked nothing like the baseball fields I’d seen on the Zenith in our family room. This field was so big and so green, a field of dreams.

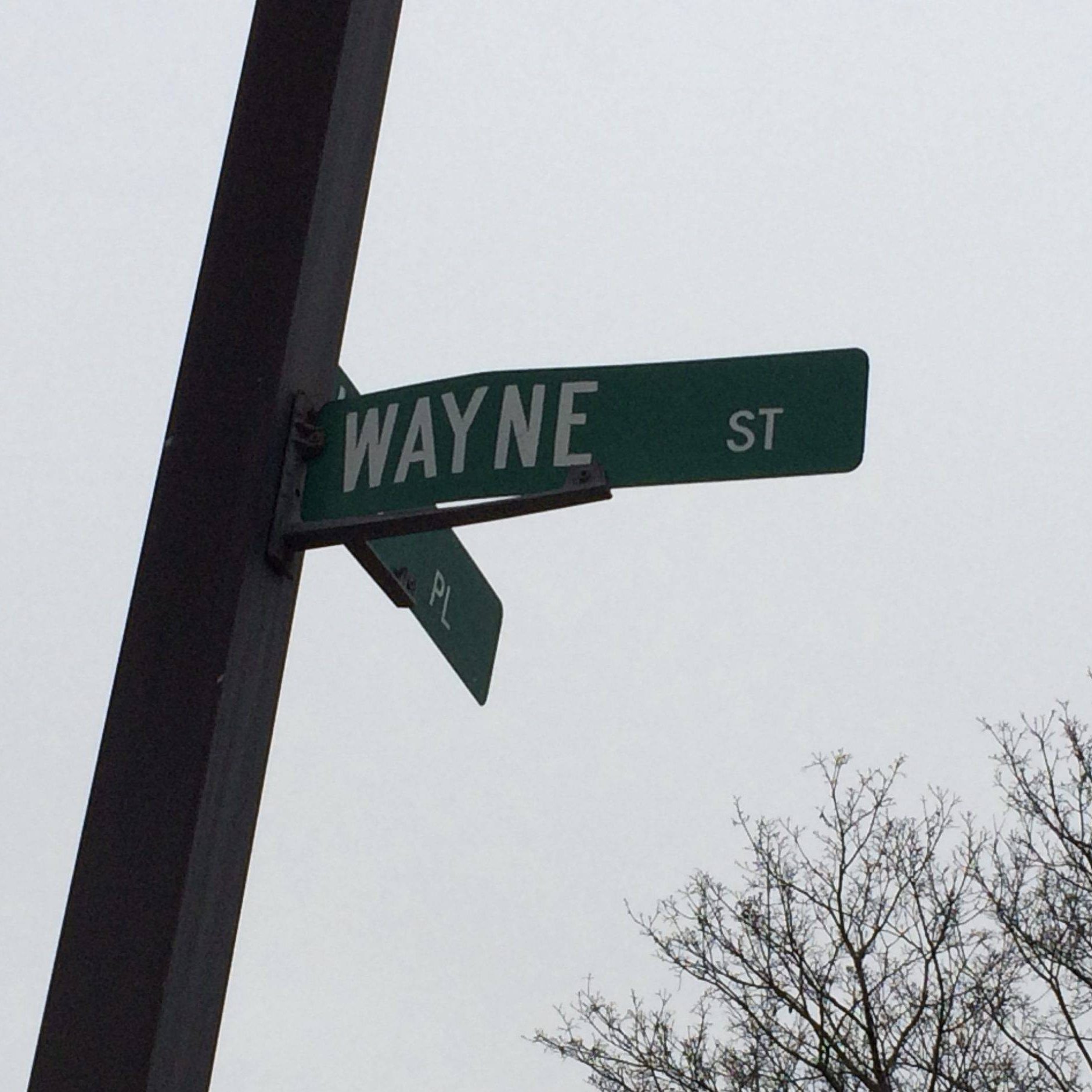

We sat in the mezzanine that afternoon. The Mets won 5-2. Jerry Koosman tossed a complete game five-hitter. Wayne Garrett belted a home run. We called him “Wayne Street” Garrett because we lived on Wayne Street.

My dad and I played catch on Wayne Street. He threw me grounders that I fielded like Buddy Harrelson and Doug Flynn. I caught his pop flies like Del Unser and Steve Henderson. I practiced pitching like I was Craig Swan and Tom Seaver.

We never used a hardball, only a tennis ball. The neighbors always parked their cars in the street, and I’d learned the hard way that baseballs and windows don’t get along.

On weeknights, I’d sit on the steps and wait for his car to turn up Wayne Street, hoping there’d be time for an after-work catch before the sun dipped behind the houses. Daylight Saving Time was my favorite time of year.

On weekends, I’d walk into his study, glove in hand, to find out when he could take a break and “come up for air.” That’s what he called it. Some days I waited hours. All days it was worth the wait.

I started playing little league in second grade. It was called the instructional league. My dad was one of my coaches, but that was the only year he could manage it because of work.

I started playing little league in second grade. It was called the instructional league. My dad was one of my coaches, but that was the only year he could manage it because of work.

I played little league all through elementary school. He tried to make my weekday practices and games, often showing up in his suit straight from work. On the nights he couldn’t, I’d wait on the front steps for his car to turn up Wayne Street. Then I’d sit at the kitchen table while he ate his dinner and tell him all about baseball.

On weekends, games started at one and four-fifteen. It was tough for him to make the early games on Saturdays, but he always made the later ones. He made the Sunday games no matter what time they started.

The games meant so much more when he was there.

Every year, we went to several Mets games.

One of my dad’s clients had a six-seat box in the loge. A couple times each season, we got to sit in it. Three seats in the first row, three seats in the second between home and third. My seat was always first row on the aisle, and I’d sit with my glove dangling over the railing because I was going to catch a foul ball.

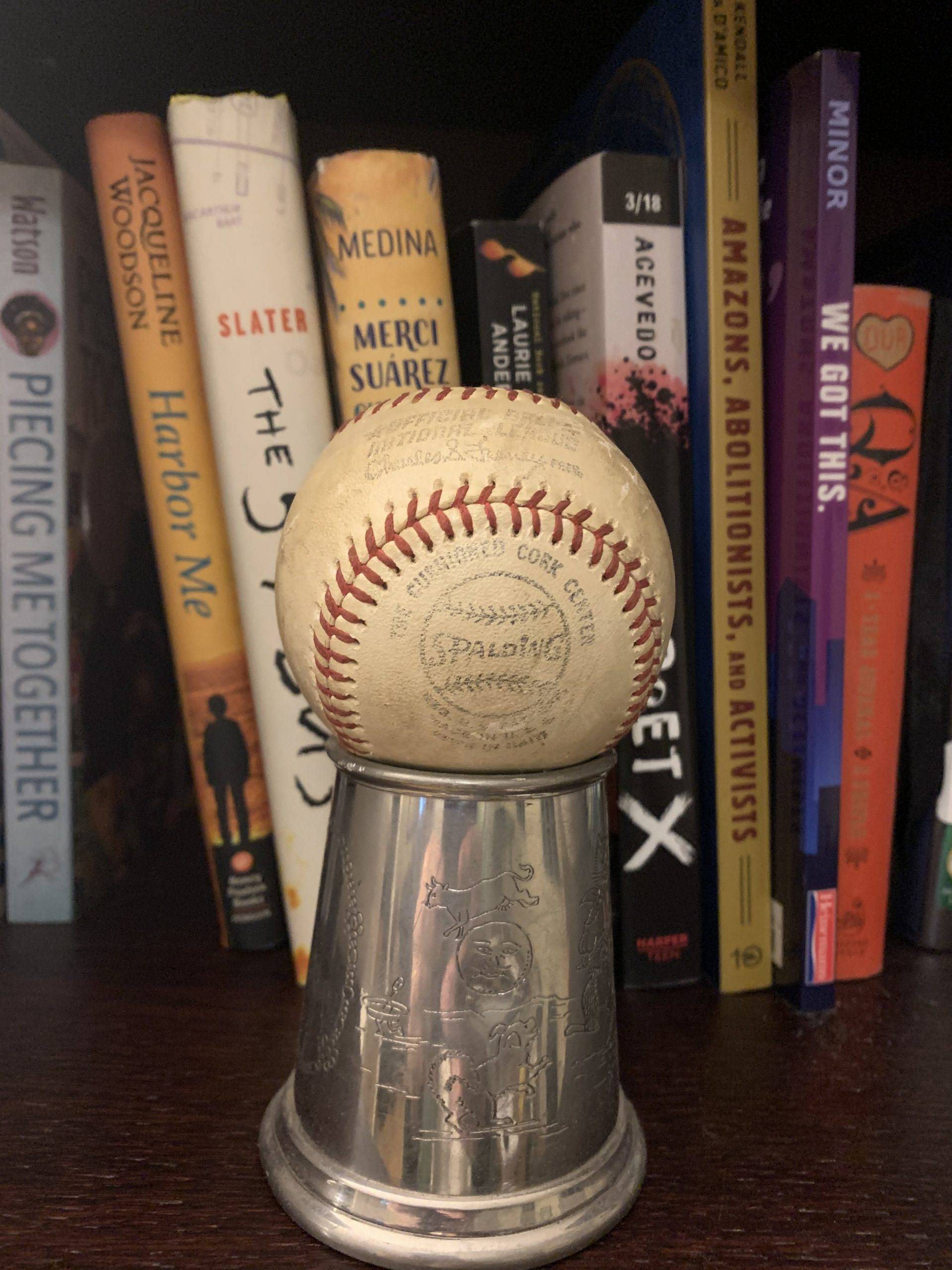

In the ninth inning on June 1, 1976, Richie Hebner fouled off Bob Myrick’s pitch right into my dad’s outstretched hand.

That ball sits on a shelf in my office.

That ball was in reach of my outstretched hand while I wrote A High Five for Glenn Burke.

My dad took me to my first opening day in 1981. The Mets beat the Cardinals on a freezing cold April 15, Tax Day. He ducked out of work early just so we could go.

I started going to every opening day, though I went with friends because weekday matinees during the first and second week of April didn’t work for Dad.

I went to dozens of games with my friends in the eighties. We’d drive to Flushing, park on College Point Boulevard, stop at my friend’s deli for heroes, and then walk across the Roosevelt Avenue Bridge to Shea. We’d buy tickets in the upper deck, and then over the course of the game, we’d sneak down to the mezzanine and loge. After the seventh, we’d wait outside the field level gates and ask the men in suits leaving early for their ticket stubs. Then we’d watch the rest of the game from our box seats.

One year, I contacted Jay Horwitz, the Mets’ legendary Public Relations Director.

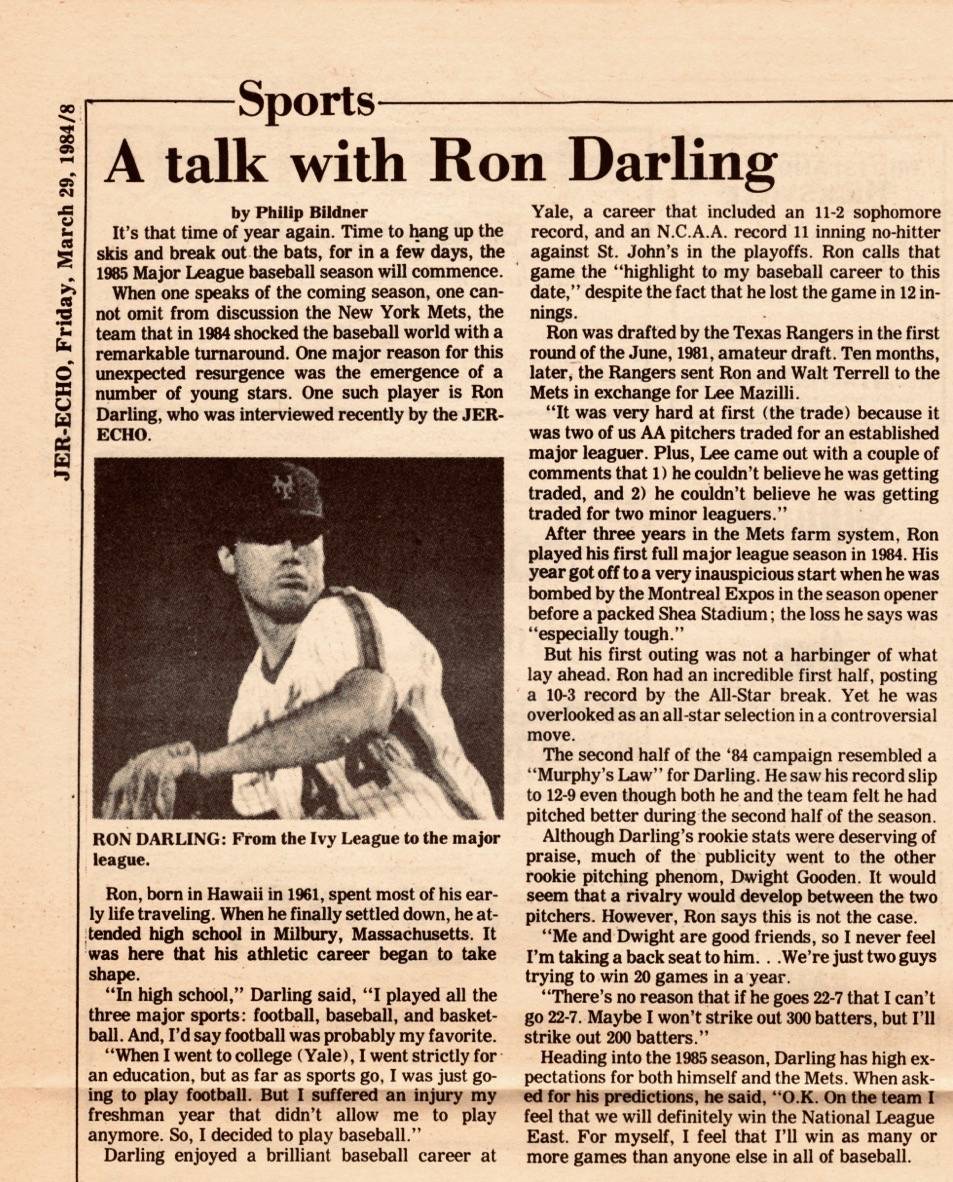

I wrote for my high school newspaper, and in the front offices at Shea Stadium, I got to interview my favorite Mets player of all, Ron Darling.

I didn’t go to opening day in 1986, the most amazin’ year in the history of the team. I was in North Shore Hospital that day. Growing up, I had a secret. I considered it a demon, a demon I was going to defeat. Because this demon couldn’t be me. It couldn’t be who I really was. It ate away at me, tormented me, and tortured me to the point where teenage me wanted to end his life.

The first time I ever saw my dad cry was opening day in 1986.

(Photo Credit: Kevin Lewis)

I came out to my dad ten years later on July 24, 1996. He was sitting at the kitchen table in the house where I grew up on Wayne Street when I told him. He was sitting in the seat where I used to watch him eat dinner while I told him all about baseball.

It was the second time I ever saw him cry.

After that day, Dad never flinched. After I told him I was gay, he never flinched. Not once, not ever.

A few years later, we went to a game at Shea and sat first row in the field level boxes. My boyfriend, Kevin, who later became my husband, went too. It was the day David Wright made his debut for the New York Mets.

Before Shea Stadium was torn down after the 2008 season, season ticket holders were given the opportunity to purchase their seats. A friend had season tickets for seats that I sat in a few times each year. He wasn’t buying his seats, so I did. I bought a pair of seats from the mezzanine. Like the seats I sat in with my dad the first time we ever went to Shea.

When Kevin and I lived in our Brooklyn loft, we kept those seats by the front door. Here in Newburgh, they’re by the front door, too. Whenever my dad visited, he always sat in them when he took off his sneakers before coming in and when he put them back on before heading out.

After saying goodbye to my dad last summer. I sat in my car in the driveway of his home on Vista Drive – he no longer lived on Wayne Street — and wrote in my journal. I needed to get down my thoughts and his last words.

As I wrote, the Dave Matthews Band version of Neil Young’s “Cortez the Killer” played in the background. The next day, I looked up the lyrics. The last line is, “I still can’t remember when or how I lost my way.” The song isn’t about memory, but it is for me. That song will always be about those eleven words.

My dad may not be able to remember, but I still can. I know how much baseball meant to him. I know how much baseball meant to us. I also know how much I meant to him.

My dad would have loved A High Five for Glenn Burke. No, it’s not a book about fathers and sons and baseball. But it is a book about love and truth and baseball. He would’ve understood its importance. More than anyone. It’s a book I never could have written if not for William Bildner.

High five, Dad.

What a beautiful “Happy recap” (in Bob Murphy’s immortal words, like I have to tell you). Having lost my father to dementia, and being a Mets fan in the same era (and a little earlier) I relate to this so strongly. Turning your pain into art that will be read and loved by kids everywhere is a precious gift. I look forward to reading it and hopefully seeing you at an event soon! – Denis

Thanks, Denis. There’s a paragraph from the post that referenced Bob Murphy but was deleted because of the length. It read,

On July 24, 1988, we sat in my dad’s client’s six-seat loge box for Tom Seaver Day, the day the Mets retired the number forty-one during a pre-game ceremony. Bob Murphy emceed the ceremonies, Suzyn Waldman sang a stirring version of “Take Me Out to the Ballgame,” and dressed in a tan suit, Tom Terrific stood on the mound and bowed to the sellout crowd.

Last year, four months before I said goodbye to my dad, Tom Seaver retired from public life. He has dementia.

Like my dad.

Oh my gosh. I actually wrote for Seaver for a benefit years ago. He was (pardon the pun) a great sport but he didn’t seem terribly interested in hearing how often I used to watch him on Kiner’s Korner (I actually googled it to make sure corner WAS spelled with a “k.”). I have to confess that I wasn’t aware of Glenn Burke before this but read up. What an amazing story…inspiring and yet so sad…

I have known Phil Bildner all his life, man and boy and proudly watched his career grow and grow. I am English so baseball is…..not quite my thing, but will look forward to reading this book which his parents will no doubt send to me in England soon. William or Bill as we know him, Bildner visited us in England last year ( we are old friends, (I was a bridesmaid at his wedding!) and although not the articulate man he used to be, he was still that lovely man who always made me laugh when he tried to copy my accent. My dear husband has Alzheimers….why does that bastard disease attack the best of brains ……but we were all able to sit and reminiss mostly about our kids, and we talked a lot about his love of baseball and we tried, not very successfully to explain the rules of cricket. Oh happy days…and Phil, he is so very proud of you and your success, as are we all. And your dear dad….a very special man.

Thanks for sharing your kind words, Gwen.

I am not a baseball fan, not even a little bit. But I’m a massive Phil Bildner fan. And now I’m a massive Phil Bildner’s Dad fan. I understand the pain of watching a parent disappear while being right there. I’m happy that evidence of your dad’s life as it once was exists still in objects both large and small. And of course, in you, Phil. How proud he must be of you…